With the commemorations of Marty McFly and Doc Brown venturing from 1985 to "the future" of October 21, 2015 winding down, another back-to-the-future moment from the 1980s is on tap for this coming week. But unlike hover boards, flying cars, or Mr. Fusion, this time the view from the 1980s understated what the future would hold.

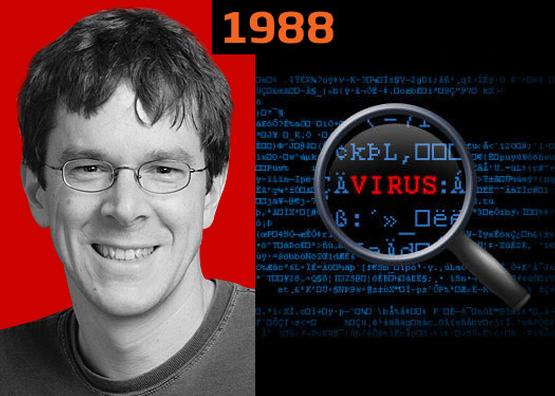

Twenty-seven years ago on November 2, 1988, Robert Morris, then a Cornell University grad student, made history by launching the first "Internet worm" from MIT. Meant, according to Morris, to gauge the size of the Internet, the worm morphed into a denial of service exploit copying itself relentlessly onto many of the 60,000 computers then connected to the still nascent Internet.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office placed the cost estimate of the damage caused by the Morris worm in the $100,000 to $10 million range given that the Internet had to be partitioned for several days to clean up the infection. As a result, Morris became the first person prosecuted under the newly enacted Computer Fraud and Abuse Act, getting three years probation and having to pay a $10,050 fine. Still, don't feel too bad for Morris. He's now a tenured professor at MIT as well as a dot-com millionaire, so things didn't turn out too poorly for the world's first "cyber attacker."

What lessons does this episode hold now nearly thirty years later?

Some things have gotten worse. It's now far more difficult to attribute cyber attacks back to a source, for example. Instead of 60,000 computers connected to the Internet, there are more than 9 billion devices of all types, from refrigerators and cars to fitness trackers. There are also more than 3 billion people now online, multiplying vulnerabilities and malicious actors.

The regulatory tools that we can use to go after cyber attackers have also failed to keep up with technological advancements, including the CFAA itself. Though the U.S. now has more than 20 cybercrime statutes on the books, the number and severity of attacks has not seemed to improve (though data is far from perfect in this regard), setting the stage for the recently passed Cyber Intelligence Sharing Act (CISA). Though this pending bill includes voluntary private-public information sharing with law enforcement in exchange for liability protections is a step forward, it is a long way from what is needed to address the multifaceted cyber threat.

Still, there is also cause for hope. One byproduct of the Morris worm was the establishment of the Cyber Emergency Response Team (CERT) based at Carnegie Mellon, a concept that has now been replicated around the world. More organizations are also taking a proactive cybersecurity stance, building in cybersecurity best practices from the start rather than bolting them on after the fact. This includes minimizing the danger of insider threats through meshing corporate and human resources policies, reviewing the cybersecurity track records of vendors and potential partners, as well as requiring NIST Framework compliance as a baseline standard.

More countries are similarly establishing an array of bottom-up and top-down regulatory frameworks to incentivize (or even require) the uptake of global cybersecurity best practices. And the good news is that there's plenty of low-hanging fruit. The Australian government, for example, has reportedly been successful in preventing 85 percent of cyber attacks through following three common sense techniques: (1) application whitelisting (only permitting pre-approved programs to operate on networks), (2) regularly patching applications and operating systems, and (3) "minimizing the number of people on a network who have 'administrator' privileges." This stuff doesn't have to be rocket science, just computer science.

Similarly, countries have come together to reach agreements on everything from the applicability of international law to cyber attacks to protecting critical infrastructure and protecting the Right to Privacy in the Digital Age, though certainly much more remains to be done. Still, these are important steps on the long march to some measure of .

Similarly, countries have come together to reach agreements on everything from the applicability of international law to cyber attacks to protecting critical infrastructure and protecting the Right to Privacy in the Digital Age, though certainly much more remains to be done. Still, these are important steps on the long march to some measure of .

What cyberspace, and the "real world," will look like another 27-years hence in 2042 remains to be seen. With concerted, polycentric efforts, even if cyber attacks remain ongoing at that point, they could be brought down to a level comparable to myriad other business and national security risks. Either way, though, we better have hover boards (with the full set of built-in cybersecurity best practices, of course; we wouldn't those things getting hacked and crashing into Clock Towers).

This article originally appeared on the Huffingtonpost as ''Another 'Back to the Future' Moment - 27 Years After the World's First Cyber Attack